Reading C declarators is notoriously confusing at first because of their convoluted syntax. This post shows how compilers interpret declarators and then present a simple heuristic for reading them as C types. If you want to go deeper, the appendix walks through a small parser and resolver that turn declarator syntax into a type description.

C language grammar and the ontology of declarators

The C grammar defines the following rules:

<declarator> ::= {<pointer>}? <direct-declarator>

<pointer> ::= * {<type-qualifier>}* {<pointer>}?

<type-qualifier> ::= const

| volatile

<direct-declarator> ::= <identifier>

| ( <declarator> )

| <direct-declarator> [ {<constant-expression>}? ] # Arrays

| <direct-declarator> ( <parameter-type-list> ) # Functions

| <direct-declarator> ( {<identifier>}* ) # old function declarators of the kind "int a(b,c,d)" (K&R style) without assigning types to the argumentsThese declarators are found in C source code to declare variables and functions. The relationship between the declarators and the declarations in C are as follows:

- Function declarators:

- Functions as per the C grammar are as follows:

<function-definition> ::= {<declaration-specifier>}* <declarator> {<declaration>}* <compound-statement>

<declaration-specifier> ::= <storage-class-specifier>

| <type-specifier>

| <type-qualifier>

- The

{<declaration>}*here can be ignored, this production corresponds to old-style K&R function definitions; rare in modern C.

int sum(a, b)

int a;

int b;

{

return a + b;

}- The modern equivalent is:

int a(int b, int c) { return b + c;}- Note that the compound statement here is

{ return b + c; } - So the declarator is limited to

a(int b, int c) - This corresponds to

<direct-declarator> ::= <direct-declarator> ( <parameter-type-list> )

- Variable declarations

- The grammar for variable declarations:

<declaration> ::= {<declaration-specifier>}+ {<init-declarator>}* ;

<init-declarator> ::= <declarator>

| <declarator> = <initializer>

<initializer> ::= <assignment-expression>

| { <initializer-list> }

| { <initializer-list> , }

<initializer-list> ::= <initializer>

| <initializer-list> , <initializer>- Let’s take an example of C source that corresponds to this grammar:

const int // declaration specifier +

a = 3, b = 5; // initializer - list and ;- You might expect to initialize a function, but C compilers throw an error in this case:

int a(int b, int c) = 0; // Compiler will throw a semantic error- The semantic error here comes from the semantic analysis pass in LLVM. Reference to source

- Pointers:

- The following C source code:

int f(int b, int c) { return b + c; }

int (*a)(int, int) =

f; // function pointer to function taking in two ints returning int

int *b = NULL; // pointer to int

int **c = &b; // pointer to a pointer to int

int *d[4] = {b, b, b, NULL}; // array of size 4 of pointer to int

int *(*e)[4] = &d; // pointer to array of size 4 of int*- Of all of these, the interesting albeit confusing examples are listed here:

int f(int b, int c) { return b + c; } // declarator here is f(int b, int c)

int (*a)(int, int) =

f; // declarator here is (*a)(int, int)

int *d[4] = {b, b, b, NULL}; // declarator here is *d[4]

int *(*e)[4] = &d; // declarator here is *(*e)[4]Reading C declarators as C types

Let’s take some examples and discuss an algorithm/heuristic for determining the type from the declarator:

int (*a)(int, int) =

f; // function pointer to function taking in two ints returning int

int *b = NULL; // pointer to int

int **c = &b; // pointer to a pointer to int

int *d[4] = {b, b, b, NULL}; // array of size 4 of pointer to int

int *(*e)[4] = &d; // pointer to array of size 4 of int*

int g[4] = {1,2,3,4}; // array of 4 integers

int (*f)[4] = &g; // pointer to array of 4 integersThe trick in reading declarators is to start peeling one layer after another from them:

int (*a)(int, int):

- The declarator here is

(*a)(int, int) - First declarator we encounter is a function pointer, so we peel it off and get

*a. Note that the outermost layerownsthe outermost type, since function arguments lie inside the outer parenthesis, the returning type here isint. Let’s keep track of the peeled declarators in a buffer:[function returning int] - The next layer is a pointer, so we peel it off and we end up with the identifier. Now our declarator is empty and the buffer left is

[function returning int, pointer] - Now reverse the buffer and append the strings, hence the buffer becomes

pointer to function returning int

int (*f[])():

- The declarator here is

(*f[])() - First declarator we encounter is a function pointer, so we peel it off and get

*f[]. Our buffer is now[function returning int]. - The next layer is a pointer, so we peel it off and we end up with a pointer, leftover declarator is

f[]. Our buffer is now[function returning int, pointer] - The next layer is an array, so we peel it off and we end up with our identifier

f. The final buffer is[function returning int, pointer, array] - Reversing and appending the strings:

array of pointer to function returning int

int (*g)[4]:

- The declarator here is

(*g)[4] - First declarator here is an array, so we peel it off and get

*g. Our buffer is now[array] - The next layer is a pointer, so we peel it off and we end up with a pointer, leftover declarator is

g. The buffer is now[array of int, pointer] - Reversing and appending the strings:

pointer to array of int

int *g[4]:

- The declarator here is

*g[4] - First declarator here is a pointer, so we peel it off and get

g[4]. The buffer is now[pointer to int] - The next layer is an array, so we peel it off and we end up with our identifier

g. The final buffer is[pointer to int, array] - Reversing and appending the strings:

array of pointer to int

The algorithm that we have mentioned here can be summarized as follows:

- Peel off the outermost layer of the declarator and append it into a buffer

- Keep doing this and collect each layer to the buffer

- Once we reach the identifier, reverse and append the strings to get the C type

If you want to go deeper, the appendix after this section will talk about how to implement the parser for declarators and how to write a resolver that walks the declarator tree and convert it into a C type as per the algorithm discussed above.

Appendix: Writing a parser and a type resolver for declarators

Writing a parser

Let’s take the examples that are discussed before:

int f(int b, int c) { return b + c; }

int (*a)(int, int) =

f; // function pointer to function taking in two ints returning int

int *b = NULL; // pointer to int

int **c = &b; // pointer to a pointer to int

int *d[4] = {b, b, b, NULL}; // array of size 4 of pointer to int

int *(*e)[4] = &d; // pointer to array of size 4 of int*Let’s translate these test cases to some typescript tests, and then try to implement our own parser based on the grammar. There are some interesting concepts involved in parsing them, so this subsection serves the purpose of explaining those ideas:

describe("parseDeclarator", () => {

test("parses function pointer assignments", () => {

expect(parseDeclarator("int (*a)(int, int)")).toEqual({

ast: {

kind: "declaration",

type: "int",

declarator: {

kind: "function",

of: {

kind: "pointer",

qualifiers: [],

to: { kind: "identifier", name: "a" },

},

params: [

{ kind: "parameter", type: "int", declarator: null },

{ kind: "parameter", type: "int", declarator: null },

],

identifiers: null,

},

},

});

});

test("parses function declarator with named params", () => {

expect(parseDeclarator("int a(int b, int c);")).toEqual({

ast: {

kind: "declaration",

type: "int",

declarator: {

kind: "function",

of: { kind: "identifier", name: "a" },

params: [

{

kind: "parameter",

type: "int",

declarator: { kind: "identifier", name: "b" },

},

{

kind: "parameter",

type: "int",

declarator: { kind: "identifier", name: "c" },

},

],

identifiers: null,

},

},

});

});

test("parses pointer to int", () => {

expect(parseDeclarator("int *b")).toEqual({

ast: {

kind: "declaration",

type: "int",

declarator: {

kind: "pointer",

qualifiers: [],

to: { kind: "identifier", name: "b" },

},

},

});

});

test("parses pointer to pointer", () => {

expect(parseDeclarator("int **c")).toEqual({

ast: {

kind: "declaration",

type: "int",

declarator: {

kind: "pointer",

qualifiers: [],

to: {

kind: "pointer",

qualifiers: [],

to: { kind: "identifier", name: "c" },

},

},

},

});

});

test("parses array of pointers", () => {

expect(parseDeclarator("int *d[4]")).toEqual({

ast: {

kind: "declaration",

type: "int",

declarator: {

kind: "pointer",

qualifiers: [],

to: {

kind: "array",

of: { kind: "identifier", name: "d" },

size: 4,

},

},

},

});

});

test("parses pointer to array of pointers", () => {

expect(parseDeclarator("int *(*e)[4]")).toEqual({

ast: {

kind: "declaration",

type: "int",

declarator: {

kind: "pointer",

qualifiers: [],

to: {

kind: "array",

of: {

kind: "pointer",

qualifiers: [],

to: { kind: "identifier", name: "e" },

},

size: 4,

},

},

},

});

});

});The AST nodes are modelled as these typescript types:

export type IdentifierNode = {

kind: "identifier";

name: string;

};

export type TypeQualifier = "const" | "volatile";

export type PointerNode = {

kind: "pointer";

qualifiers: TypeQualifier[];

to: DeclaratorNode;

};

export type ArrayNode = {

kind: "array";

of: DeclaratorNode;

size: number | null;

};

export type FunctionNode = {

kind: "function";

of: DeclaratorNode;

params: ParameterNode[] | null;

identifiers: string[] | null;

};

export type DeclaratorNode =

| IdentifierNode

| PointerNode

| ArrayNode

| FunctionNode;

export type TypeSpecifier = "int";

export type ParameterNode = {

kind: "parameter";

type: TypeSpecifier;

declarator: DeclaratorNode | null;

};

export type DeclarationNode = {

kind: "declaration";

type: TypeSpecifier;

declarator: DeclaratorNode;

};- The

DeclaratorNodehere represents the following:

Identifiers: a plain stringint a = 3 // declarator here is "a"Pointers: a pointer declaratorint *a = NULL // declarator here is "*a"ArrayNode: an array declaratorint a[2] = {1,2}; // declarator here is "a[2]FunctionNode: declarators of suchint a(int b,int c) // declarator here is a(int b,int c)and function pointersint (*a)(int b,int c) // declarator here is (*a)(int b, int c)

- Once we have the parsed data structure, we will write a stringify function that returns the string similar to what is shown in the meme

- We expect the following output for this program:

if (import.meta.main) {

const parsed = parseDeclarator("int (*(*x[])())()");

console.log(

"int (*(*x[])())()",

JSON.stringify(stringify(parsed.ast), null, 2)

);

}Gives:

int (*(*x[])())() defines x as array of unspecified size of pointer to function returning pointer to function returning int.So if we implement parseDeclarator then we truly understand how declarators are parsed and interpreted. The obvious problem with parsing productions of this kind:

<direct-declarator> ::= <identifier>

| ( <declarator> )

| <direct-declarator> [ {<constant-expression>}? ]

| <direct-declarator> ( <parameter-type-list> )

| <direct-declarator> ( {<identifier>}* )These productions are left recursive, for example if we wrote the parser in our usual recursive style, we get the following:

function parseDirectDeclarator() {

parseDirectDeclarator(); // Infinite recursion

}So the productions here are not parsable via a trivial recursive descent parser. However we can use a simple trick to rewrite the grammar to a non-left-recursive one. Let’s take a general case with grammar:

A -> base | A suffixThis can be rewritten as:

A -> base (suffix)*Hence our grammar becomes:

<suffix> ::= [ {<constant-expression>}? ] | ( <parameter-type-list> ) | ( {<identifier>}* )

<base> ::= <identifier> | ( <declarator> )

<direct-declarator> ::= <base> (<suffix>)*This grammar is easier to parse via a recursive descent parser. I don’t really want to write the entire parser here, the source code for this including the pretty printer can be found here

Parse trees to a C Type

Let’s translate our previous algorithm to typescript using our existing ast types. The flattenAST function creates the buffer as per our earlier algorithm and stringify reverses the buffer and joins the strings to create the string representation of the C type obtained.

export const flattenAST = (

ast: DeclarationNode

): {

declaratorQueue: Array<"array" | "pointer" | "function">;

declaratorName: string;

baseType: string;

} => {

let runner = ast.declarator;

let queue: Array<"array" | "pointer" | "function"> = [];

while (runner.kind != "identifier") {

switch (runner.kind) {

case "array": {

runner = runner.of;

queue.push("array");

break;

}

case "pointer": {

runner = runner.to;

queue.push("pointer");

break;

}

case "function": {

runner = runner.of;

queue.push("function");

break;

}

}

}

return {

declaratorQueue: queue,

declaratorName: runner.name,

baseType: ast.type,

};

};

export const stringify = (ast: DeclarationNode): String => {

const { declaratorQueue, declaratorName, baseType } = flattenAST(ast);

console.log({ declaratorQueue });

const str = declaratorQueue.reverse().reduce((prev, current) => {

switch (current) {

case "array": {

return `${prev} array of `;

}

case "pointer": {

return `${prev} pointer to `;

}

case "function": {

return `${prev} function returning `;

}

}

}, "");

return `${declaratorName} is ${str} ${baseType}`;

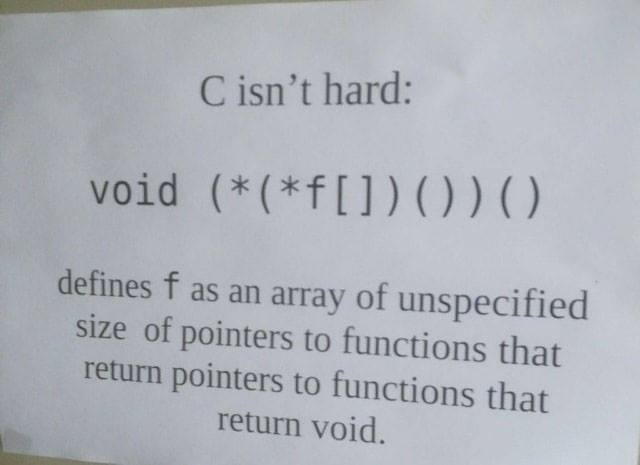

};Deriving the meme

The declarator as per the meme is int (*(*f[])())(). Passing this to our stringify function gives us the following output:

> bun run index.ts

{

declaratorQueue: [ "function", "pointer", "function", "pointer", "array" ],

}

int (*(*x[])())() "f is array of pointer to function returning pointer to function returning int"which is the same as: f is an array of unspecified size of pointers to functions that return pointers to functions that return int